View on TensorFlow.org View on TensorFlow.org

|

Run in Google Colab Run in Google Colab

|

View source on GitHub View source on GitHub

|

Download notebook Download notebook

|

This tutorial shows how a classical neural network can learn to correct qubit calibration errors. It introduces Cirq, a Python framework to create, edit, and invoke Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) circuits, and demonstrates how Cirq interfaces with TensorFlow Quantum.

Setup

pip install tensorflow==2.15.0Install TensorFlow Quantum:

pip install tensorflow-quantum==0.7.3# Update package resources to account for version changes.

import importlib, pkg_resources

importlib.reload(pkg_resources)

/tmpfs/tmp/ipykernel_23649/2730622109.py:2: DeprecationWarning: pkg_resources is deprecated as an API. See https://setuptools.pypa.io/en/latest/pkg_resources.html import importlib, pkg_resources <module 'pkg_resources' from '/tmpfs/src/tf_docs_env/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pkg_resources/__init__.py'>

Now import TensorFlow and the module dependencies:

import tensorflow as tf

import tensorflow_quantum as tfq

import cirq

import sympy

import numpy as np

# visualization tools

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from cirq.contrib.svg import SVGCircuit

2025-01-10 12:30:52.812632: E external/local_xla/xla/stream_executor/cuda/cuda_dnn.cc:9261] Unable to register cuDNN factory: Attempting to register factory for plugin cuDNN when one has already been registered 2025-01-10 12:30:52.812677: E external/local_xla/xla/stream_executor/cuda/cuda_fft.cc:607] Unable to register cuFFT factory: Attempting to register factory for plugin cuFFT when one has already been registered 2025-01-10 12:30:52.814351: E external/local_xla/xla/stream_executor/cuda/cuda_blas.cc:1515] Unable to register cuBLAS factory: Attempting to register factory for plugin cuBLAS when one has already been registered 2025-01-10 12:30:55.797370: E external/local_xla/xla/stream_executor/cuda/cuda_driver.cc:274] failed call to cuInit: CUDA_ERROR_NO_DEVICE: no CUDA-capable device is detected

1. The Basics

1.1 Cirq and parameterized quantum circuits

Before exploring TensorFlow Quantum (TFQ), let's look at some Cirq basics. Cirq is a Python library for quantum computing from Google. You use it to define circuits, including static and parameterized gates.

Cirq uses SymPy symbols to represent free parameters.

a, b = sympy.symbols('a b')

The following code creates a two-qubit circuit using your parameters:

# Create two qubits

q0, q1 = cirq.GridQubit.rect(1, 2)

# Create a circuit on these qubits using the parameters you created above.

circuit = cirq.Circuit(cirq.rx(a).on(q0), cirq.ry(b).on(q1), cirq.CNOT(q0, q1))

SVGCircuit(circuit)

findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found.

To evaluate circuits, you can use the cirq.Simulator interface. You replace free parameters in a circuit with specific numbers by passing in a cirq.ParamResolver object. The following code calculates the raw state vector output of your parameterized circuit:

# Calculate a state vector with a=0.5 and b=-0.5.

resolver = cirq.ParamResolver({a: 0.5, b: -0.5})

output_state_vector = cirq.Simulator().simulate(circuit,

resolver).final_state_vector

output_state_vector

array([ 0.9387913 +0.j , -0.23971277+0.j ,

0. +0.06120872j, 0. -0.23971277j], dtype=complex64)

State vectors are not directly accessible outside of simulation (notice the complex numbers in the output above). To be physically realistic, you must specify a measurement, which converts a state vector into a real number that classical computers can understand. Cirq specifies measurements using combinations of the Pauli operators \(\hat{X}\), \(\hat{Y}\), and \(\hat{Z}\). As illustration, the following code measures \(\hat{Z}_0\) and \(\frac{1}{2}\hat{Z}_0 + \hat{X}_1\) on the state vector you just simulated:

z0 = cirq.Z(q0)

qubit_map = {q0: 0, q1: 1}

z0.expectation_from_state_vector(output_state_vector, qubit_map).real

0.8775825500488281

z0x1 = 0.5 * z0 + cirq.X(q1)

z0x1.expectation_from_state_vector(output_state_vector, qubit_map).real

-0.04063427448272705

1.2 Quantum circuits as tensors

TensorFlow Quantum (TFQ) provides tfq.convert_to_tensor, a function that converts Cirq objects into tensors. This allows you to send Cirq objects to our quantum layers and quantum ops. The function can be called on lists or arrays of Cirq Circuits and Cirq Paulis:

# Rank 1 tensor containing 1 circuit.

circuit_tensor = tfq.convert_to_tensor([circuit])

print(circuit_tensor.shape)

print(circuit_tensor.dtype)

(1,) <dtype: 'string'>

This encodes the Cirq objects as tf.string tensors that tfq operations decode as needed.

# Rank 1 tensor containing 2 Pauli operators.

pauli_tensor = tfq.convert_to_tensor([z0, z0x1])

pauli_tensor.shape

TensorShape([2])

1.3 Batching circuit simulation

TFQ provides methods for computing expectation values, samples, and state vectors. For now, let's focus on expectation values.

The highest-level interface for calculating expectation values is the tfq.layers.Expectation layer, which is a tf.keras.Layer. In its simplest form, this layer is equivalent to simulating a parameterized circuit over many cirq.ParamResolvers; however, TFQ allows batching following TensorFlow semantics, and circuits are simulated using efficient C++ code.

Create a batch of values to substitute for our a and b parameters:

batch_vals = np.array(np.random.uniform(0, 2 * np.pi, (5, 2)), dtype=float)

Batching circuit execution over parameter values in Cirq requires a loop:

cirq_results = []

cirq_simulator = cirq.Simulator()

for vals in batch_vals:

resolver = cirq.ParamResolver({a: vals[0], b: vals[1]})

final_state_vector = cirq_simulator.simulate(circuit,

resolver).final_state_vector

cirq_results.append([

z0.expectation_from_state_vector(final_state_vector, {

q0: 0,

q1: 1

}).real

])

print('cirq batch results: \n {}'.format(np.array(cirq_results)))

cirq batch results: [[-0.99993825] [-0.96574926] [ 0.53859347] [ 0.98195112] [-0.9249239 ]]

The same operation is simplified in TFQ:

tfq.layers.Expectation()(circuit,

symbol_names=[a, b],

symbol_values=batch_vals,

operators=z0)

<tf.Tensor: shape=(5, 1), dtype=float32, numpy=

array([[-0.99993825],

[-0.96574897],

[ 0.53859305],

[ 0.9819516 ],

[-0.9249234 ]], dtype=float32)>

2. Hybrid quantum-classical optimization

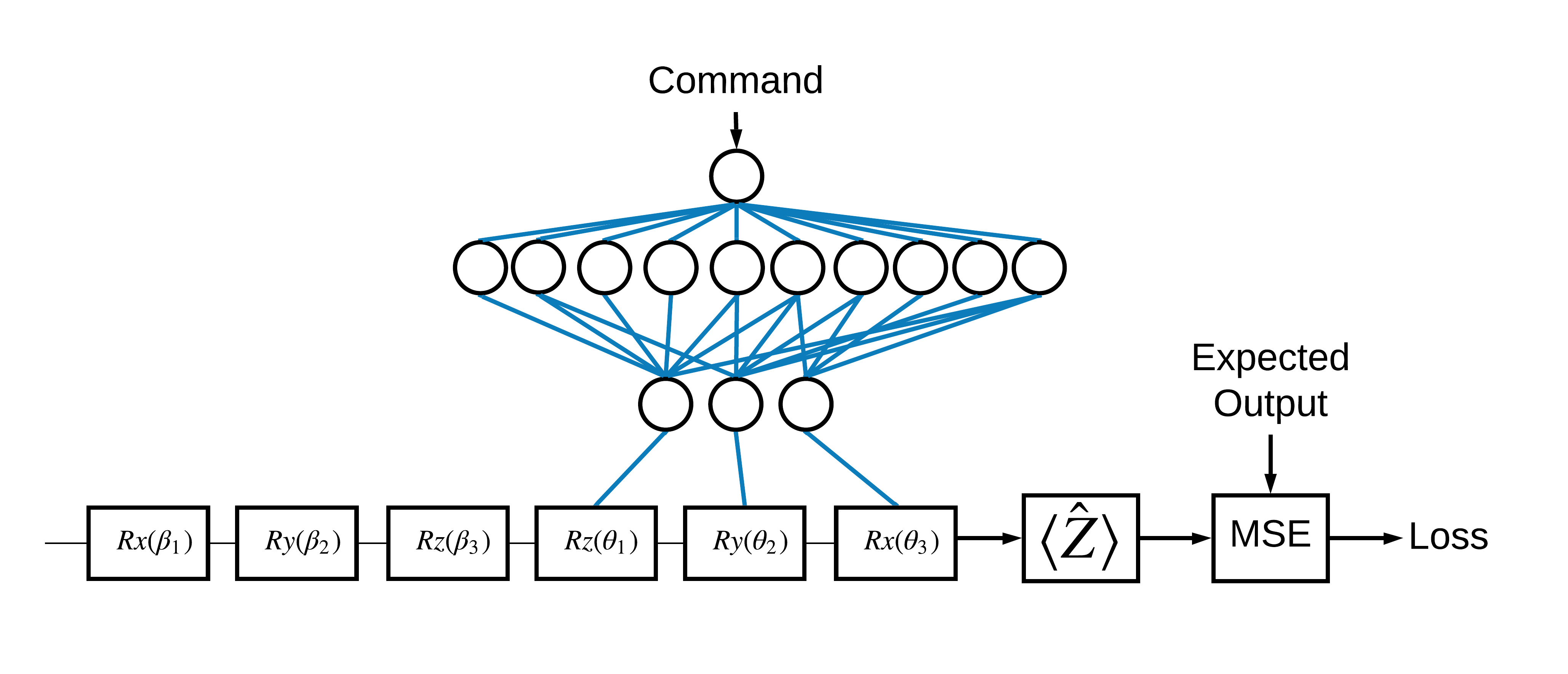

Now that you've seen the basics, let's use TensorFlow Quantum to construct a hybrid quantum-classical neural net. You will train a classical neural net to control a single qubit. The control will be optimized to correctly prepare the qubit in the 0 or 1 state, overcoming a simulated systematic calibration error. This figure shows the architecture:

Even without a neural network this is a straightforward problem to solve, but the theme is similar to the real quantum control problems you might solve using TFQ. It demonstrates an end-to-end example of a quantum-classical computation using the tfq.layers.ControlledPQC (Parametrized Quantum Circuit) layer inside of a tf.keras.Model.

For the implementation of this tutorial, this architecture is split into 3 parts:

- The input circuit or datapoint circuit: The first three \(R\) gates.

- The controlled circuit: The other three \(R\) gates.

- The controller: The classical neural-network setting the parameters of the controlled circuit.

2.1 The controlled circuit definition

Define a learnable single bit rotation, as indicated in the figure above. This will correspond to our controlled circuit.

# Parameters that the classical NN will feed values into.

control_params = sympy.symbols('theta_1 theta_2 theta_3')

# Create the parameterized circuit.

qubit = cirq.GridQubit(0, 0)

model_circuit = cirq.Circuit(

cirq.rz(control_params[0])(qubit),

cirq.ry(control_params[1])(qubit),

cirq.rx(control_params[2])(qubit))

SVGCircuit(model_circuit)

findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found. findfont: Font family 'Arial' not found.

2.2 The controller

Now define controller network:

# The classical neural network layers.

controller = tf.keras.Sequential(

[tf.keras.layers.Dense(10, activation='elu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(3)])

Given a batch of commands, the controller outputs a batch of control signals for the controlled circuit.

The controller is randomly initialized so these outputs are not useful, yet.

controller(tf.constant([[0.0], [1.0]])).numpy()

array([[ 0. , 0. , 0. ],

[-0.933574 , 0.11334291, 0.2570168 ]], dtype=float32)

2.3 Connect the controller to the circuit

Use tfq to connect the controller to the controlled circuit, as a single keras.Model.

See the Keras Functional API guide for more about this style of model definition.

First define the inputs to the model:

# This input is the simulated miscalibration that the model will learn to correct.

circuits_input = tf.keras.Input(

shape=(),

# The circuit-tensor has dtype `tf.string`

dtype=tf.string,

name='circuits_input')

# Commands will be either `0` or `1`, specifying the state to set the qubit to.

commands_input = tf.keras.Input(shape=(1,),

dtype=tf.dtypes.float32,

name='commands_input')

Next apply operations to those inputs, to define the computation.

dense_2 = controller(commands_input)

# TFQ layer for classically controlled circuits.

expectation_layer = tfq.layers.ControlledPQC(

model_circuit,

# Observe Z

operators=cirq.Z(qubit))

expectation = expectation_layer([circuits_input, dense_2])

Now package this computation as a tf.keras.Model:

# The full Keras model is built from our layers.

model = tf.keras.Model(inputs=[circuits_input, commands_input],

outputs=expectation)

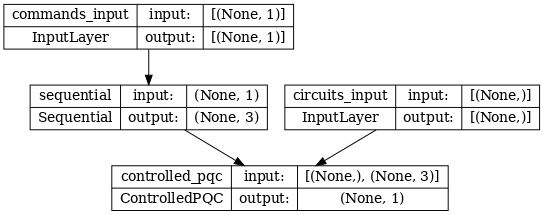

The network architecture is indicated by the plot of the model below. Compare this model plot to the architecture diagram to verify correctness.

tf.keras.utils.plot_model(model, show_shapes=True, dpi=70)

This model takes two inputs: The commands for the controller, and the input-circuit whose output the controller is attempting to correct.

2.4 The dataset

The model attempts to output the correct correct measurement value of \(\hat{Z}\) for each command. The commands and correct values are defined below.

# The command input values to the classical NN.

commands = np.array([[0], [1]], dtype=np.float32)

# The desired Z expectation value at output of quantum circuit.

expected_outputs = np.array([[1], [-1]], dtype=np.float32)

This is not the entire training dataset for this task. Each datapoint in the dataset also needs an input circuit.

2.4 Input circuit definition

The input-circuit below defines the random miscalibration the model will learn to correct.

random_rotations = np.random.uniform(0, 2 * np.pi, 3)

noisy_preparation = cirq.Circuit(

cirq.rx(random_rotations[0])(qubit),

cirq.ry(random_rotations[1])(qubit),

cirq.rz(random_rotations[2])(qubit))

datapoint_circuits = tfq.convert_to_tensor([noisy_preparation] *

2) # Make two copied of this circuit

There are two copies of the circuit, one for each datapoint.

datapoint_circuits.shape

TensorShape([2])

2.5 Training

With the inputs defined you can test-run the tfq model.

model([datapoint_circuits, commands]).numpy()

array([[0.9958177 ],

[0.98207647]], dtype=float32)

Now run a standard training process to adjust these values towards the expected_outputs.

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.05)

loss = tf.keras.losses.MeanSquaredError()

model.compile(optimizer=optimizer, loss=loss)

history = model.fit(x=[datapoint_circuits, commands],

y=expected_outputs,

epochs=30,

verbose=0)

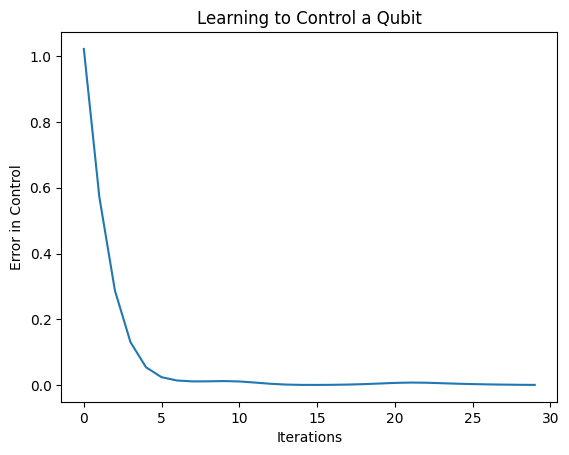

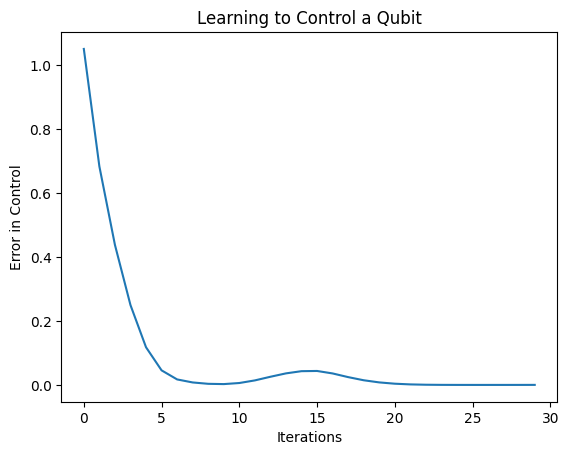

plt.plot(history.history['loss'])

plt.title("Learning to Control a Qubit")

plt.xlabel("Iterations")

plt.ylabel("Error in Control")

plt.show()

From this plot you can see that the neural network has learned to overcome the systematic miscalibration.

2.6 Verify outputs

Now use the trained model, to correct the qubit calibration errors. With Cirq:

def check_error(command_values, desired_values):

"""Based on the value in `command_value` see how well you could prepare

the full circuit to have `desired_value` when taking expectation w.r.t. Z."""

params_to_prepare_output = controller(command_values).numpy()

full_circuit = noisy_preparation + model_circuit

# Test how well you can prepare a state to get expectation the expectation

# value in `desired_values`

for index in [0, 1]:

state = cirq_simulator.simulate(full_circuit, {

s: v

for (s, v) in zip(control_params, params_to_prepare_output[index])

}).final_state_vector

expt = cirq.Z(qubit).expectation_from_state_vector(state, {

qubit: 0

}).real

print(

f'For a desired output (expectation) of {desired_values[index]} with'

f' noisy preparation, the controller\nnetwork found the following '

f'values for theta: {params_to_prepare_output[index]}\nWhich gives an'

f' actual expectation of: {expt}\n')

check_error(commands, expected_outputs)

For a desired output (expectation) of [1.] with noisy preparation, the controller network found the following values for theta: [-0.12697363 0.2161613 -0.43002388] Which gives an actual expectation of: 0.8917269706726074 For a desired output (expectation) of [-1.] with noisy preparation, the controller network found the following values for theta: [-0.39836413 0.28400192 3.2667234 ] Which gives an actual expectation of: -0.9761434197425842

The value of the loss function during training provides a rough idea of how well the model is learning. The lower the loss, the closer the expectation values in the above cell is to desired_values. If you aren't as concerned with the parameter values, you can always check the outputs from above using tfq:

model([datapoint_circuits, commands])

<tf.Tensor: shape=(2, 1), dtype=float32, numpy=

array([[ 0.8917272],

[-0.9761431]], dtype=float32)>

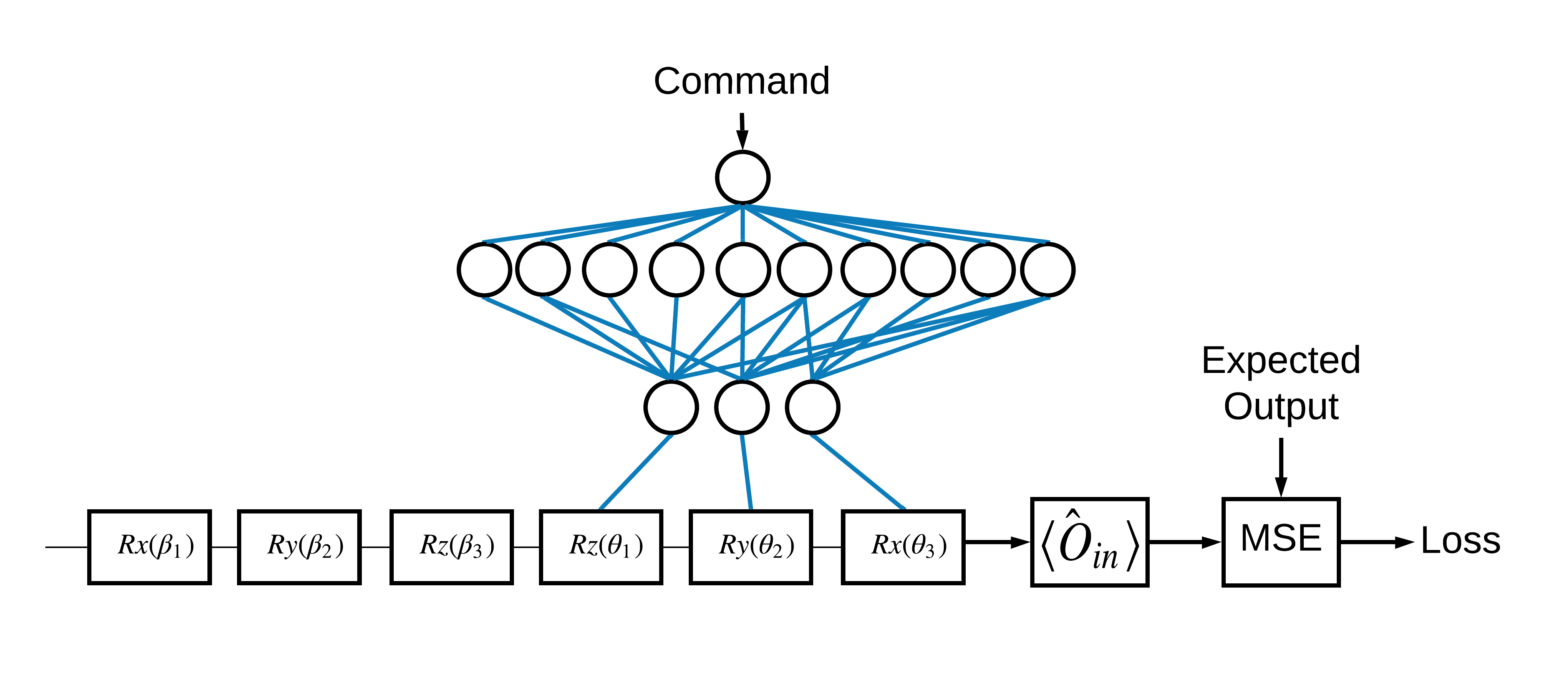

3 Learning to prepare eigenstates of different operators

The choice of the \(\pm \hat{Z}\) eigenstates corresponding to 1 and 0 was arbitrary. You could have just as easily wanted 1 to correspond to the \(+ \hat{Z}\) eigenstate and 0 to correspond to the \(-\hat{X}\) eigenstate. One way to accomplish this is by specifying a different measurement operator for each command, as indicated in the figure below:

This requires use of tfq.layers.Expectation. Now your input has grown to include three objects: circuit, command, and operator. The output is still the expectation value.

3.1 New model definition

Lets take a look at the model to accomplish this task:

# Define inputs.

commands_input = tf.keras.layers.Input(shape=(1),

dtype=tf.dtypes.float32,

name='commands_input')

circuits_input = tf.keras.Input(

shape=(),

# The circuit-tensor has dtype `tf.string`

dtype=tf.dtypes.string,

name='circuits_input')

operators_input = tf.keras.Input(shape=(1,),

dtype=tf.dtypes.string,

name='operators_input')

Here is the controller network:

# Define classical NN.

controller = tf.keras.Sequential(

[tf.keras.layers.Dense(10, activation='elu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(3)])

Combine the circuit and the controller into a single keras.Model using tfq:

dense_2 = controller(commands_input)

# Since you aren't using a PQC or ControlledPQC you must append

# your model circuit onto the datapoint circuit tensor manually.

full_circuit = tfq.layers.AddCircuit()(circuits_input, append=model_circuit)

expectation_output = tfq.layers.Expectation()(full_circuit,

symbol_names=control_params,

symbol_values=dense_2,

operators=operators_input)

# Contruct your Keras model.

two_axis_control_model = tf.keras.Model(

inputs=[circuits_input, commands_input, operators_input],

outputs=[expectation_output])

3.2 The dataset

Now you will also include the operators you wish to measure for each datapoint you supply for model_circuit:

# The operators to measure, for each command.

operator_data = tfq.convert_to_tensor([[cirq.X(qubit)], [cirq.Z(qubit)]])

# The command input values to the classical NN.

commands = np.array([[0], [1]], dtype=np.float32)

# The desired expectation value at output of quantum circuit.

expected_outputs = np.array([[1], [-1]], dtype=np.float32)

3.3 Training

Now that you have your new inputs and outputs you can train once again using keras.

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.05)

loss = tf.keras.losses.MeanSquaredError()

two_axis_control_model.compile(optimizer=optimizer, loss=loss)

history = two_axis_control_model.fit(

x=[datapoint_circuits, commands, operator_data],

y=expected_outputs,

epochs=30,

verbose=1)

Epoch 1/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 448ms/step - loss: 2.1220 Epoch 2/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 1.1681 Epoch 3/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.4768 Epoch 4/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.2370 Epoch 5/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.1323 Epoch 6/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.1373 Epoch 7/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.2637 Epoch 8/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.3070 Epoch 9/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.2497 Epoch 10/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.1425 Epoch 11/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0502 Epoch 12/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0089 Epoch 13/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 6.0734e-04 Epoch 14/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 1.4278e-04 Epoch 15/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 5.3596e-04 Epoch 16/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0045 Epoch 17/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0149 Epoch 18/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0298 Epoch 19/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0435 Epoch 20/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0502 Epoch 21/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0482 Epoch 22/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0395 Epoch 23/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0283 Epoch 24/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0183 Epoch 25/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0115 Epoch 26/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0080 Epoch 27/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0067 Epoch 28/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0064 Epoch 29/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0063 Epoch 30/30 1/1 [==============================] - 0s 4ms/step - loss: 0.0059

plt.plot(history.history['loss'])

plt.title("Learning to Control a Qubit")

plt.xlabel("Iterations")

plt.ylabel("Error in Control")

plt.show()

The loss function has dropped to zero.

The controller is available as a stand-alone model. Call the controller, and check its response to each command signal. It would take some work to correctly compare these outputs to the contents of random_rotations.

controller.predict(np.array([0, 1]))

1/1 [==============================] - 0s 61ms/step

array([[1.6359813 , 2.0209079 , 0.9253092 ],

[4.635884 , 0.11778158, 3.192774 ]], dtype=float32)